A Liquid Revolution: For a community without Money, Management, and Political Representation, a we-can-do-it-ourselves economy, a for-free economy

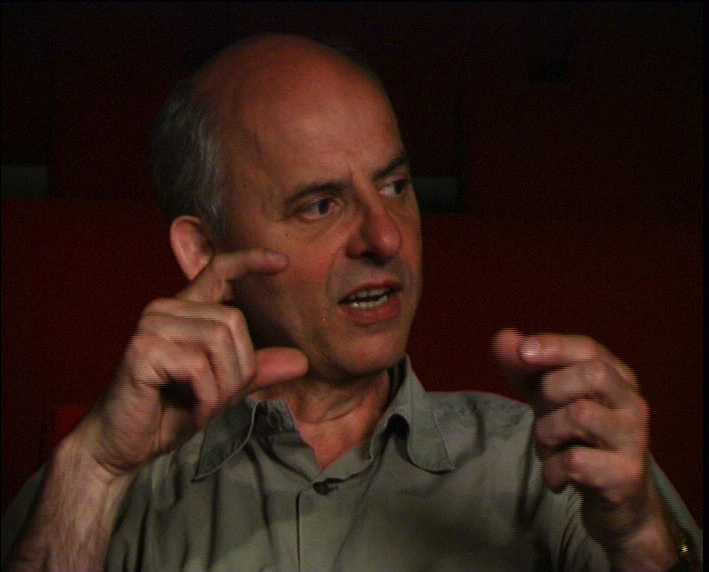

Jan Ritsema

—

Or why aren’t we allowed to do nothing and still do, as WE CANNOT NOT DO? Or why can’t we escape, or at least strongly reduce, the be-paid-for-work economy, the be-paid-too-little for selling-your-time economy?

We need an economy centered on sustainable abundance rather than scarcity. Fifty years from now our grandchildren may look at this mass-market employment with the same disbelief with which we look upon slavery and serfdom. The idea that a human being’s worth was measured almost exclusively by her or his productive output of goods, services, and material wealth will for our grandchildren seem ancient, even barbaric.

Despite thinking that we are free and liberated individuals, that we have the free will to navigate through the desert of desires we are swimming in, we still emphatically accept the only and ‘free’ choice that is offered to us, the one that is called “free labor” in the paid-too-little-for-selling-your-time economy. This profit-oriented economy is managed not for the well-being of the living workforce, but, to the contrary, it is managed efficiently to be as profitable as possible for the dead invested Capital. We are well aware that we cannot live properly when we cannot pay our bills, so we have no other choice than to work.

We think that we are free and liberated individuals, however, practically, we are not. What counts is the practice, what counts are the facts. And the factual situation is that we have no choice. We are forced to work—not in the old-fashioned brutal way; not physically, like slaves—and we have lost, or, more accurately, we have given away, our independence, by putting our resources on sale. The main resources we had were the others: the family, the tribe, the commune, the communal, the common, and public space. We exchanged these for the emperor’s new clothes by embracing the collective illusion of the free and liberated individual, who, yes, has the choice between fifty different flavors of chocolate and thirty of yogurt, but only when they can pay for it. And we, at least the majority of us who do not belong to the super-rich 1 percent, can only pay when we sell our time and space in the form of employment contracts. Having no choice equals what one could call a form of slavery, it is soft, but it is slavery nonetheless.

This slavery to which almost everybody surrenders her- or himself to is not self-evident, un-escapable, to be taken for granted, it’s given! But we can undo ourselves from it, and without becoming slaves to ourselves—to that scheme into which neoliberal capitalism tries to maneuver us. I am talking here of the 24/7 economy that neoliberalism is careering toward, in which everybody is organizing their own time and space, in order to decide all by themselves when and where they will work. This sounds good, were it not that competition will be organized in such a way that people will work twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, with all of the benefits remaining with the ones who coordinate and manage the ever-renewing chain of products and services, aka the traffic of human and machinic activity. Artists seem to be the explorers, the guinea pigs, and the teasers for this new economy. They are the representatives of those people who are mastering their own time and space: this looks like paradise were it not that they occupy themselves continuously, seemingly free, barely paid, desperately writing applications, free and precarious.

This text proposes to elaborate on this situation in order to design a way out of this trap that we illusively stepped into from the beginning of the renaissance [sic], with its invention of banks, the stock exchange, the creation of cities, etc., through the industrial age, with its massive separation of labor and capital, which got us locked in the trap completely, to our days of cognitive and semio-capitalism that drives us into co-opting/enjoying life in a cage through the creation of an almost infinite amount of desires and fears. The resulting addiction to over consumption renders inescapable the necessity to earn money to afford things or to sell future income as debt when one’s current income is barely enough to pay for housing, food, communication, insurance, and transportation. A vicious cycle, yes, that, while circling around, creates as collateral damage a lot of waste and pollution, for which the trapped have to pay too. En-cage-d, yes, with ourselves and our defensive attitude toward others.

And this is not all. The gap between the ‘haves’ and the ‘almost-have-nots’ is growing. As Oxfam stated at the World Economic Forum held in 2104 in Davos, Switzerland in their report, “Working for the Few”:

- Almost half of the world’s wealth is now owned by just one percent of the population.

- The wealth of the one percent richest people in the world amounts to $110 trillion. That’s 65 times the total wealth of the bottom half of the world’s population.

- The bottom half of the world’s population owns the same as the richest 85 people in the world.

- Seven out of ten people live in countries where economic inequality has increased in the last 30 years.

- The richest one percent increased their share of income in 24 out of 26 countries for which we have data between 1980 and 2012.

- In the US, the wealthiest one percent captured 95 percent of post-financial crisis growth since 2009, while the bottom 90 percent became poorer.[1]

They (the 1%) make their money in financials on stock markets and derivative markets for which we have thus far been paying the bills by letting them use our capability to assume debt and pay taxes as the main raw material for the accumulation of financial assets. All this is embedded in a competitive culture of fear. Unmoored from our resources, we seem to be destined to remain under these conditions forever—despite knowing that we are conditioning these conditions (and not some system or power outside of ourselves), despite knowing that only we, we ourselves, can get ourselves out of this, we still feel unable to do so. We seem fundamentally separated from each other, individualized, and by way of this we have become forceless. These conditions seem bigger than us. Yes, we are trapped. We are slaves and we are trapped. How can we get out of here?

I think only intelligence can get us out of here, only a thorough understanding of the situation together with the creation of instruments that force us into other practices can shift us into a much kinder, less violent, post-capitalist society.

An intelligent global society will find a way out of being trapped in Capital. We can imagine kind alternatives, ones that can do without barbaric exploitation and usurpation. And we can do this without losing the high standards of living many of us cling to, without losing our capacity to realize and produce new inventions and imaginings.

NO FEAR FOR THE OTHERFor this we will have to change our practices. But how can we do this in a way that we perceive as self-evident? How can we dissolve our fear of the other? The times that gave rise to Sartre’s infamous formula that l’enfer c’est les autres [hell is other people], from his theatre play Huis Clos (No Exit, 1944), are almost over. People share more time and space and knowledge and information. New technologies are very helpful here. For example, the huge for-free economy on the Internet and the (unfortunately) commercialized sharing-services economy of couching surfing, Airbnb, and the co-sharing of cars. At least some kind of Rational Altruism is slowly taking over. The beliefs that the welfare and well-being of others benefits your welfare and well-being; that your health is better when others are healthy too; that your education can be more productive when others are also well educated; that your computer becomes more valuable when others also have one; and that your economy runs better when others can enter your market as well. But this sharing-services economy reduces the fear of the other only by way of the knowledge that she or he is traceable.

The fear of the other is the fear of being disempowered by the other, by the destructive capacity of the other who is able to take away or destabilize your vulnerable mental, physical, and economical well-being and wealth. In other words, the fear of how the other can harm you, in general, the fear of what the other can do to you. The fear of the other is related to the fear of oneself. The fear of oneself is the doubt over one’s own capacities to sustain and improve one’s wealth and well-being. Will I be able to get a job or to keep my job? Will I be able to improve my position? Will I be able to pay the bills that come with my standard of living? Will I be able to keep my health, my wealth, and my relationships? Will I be able to avoid major accidents, like the unexpected destruction of my property (house, car, etc.) and prevent harm to my valuable loved ones? I am aware that these fears operate and are operated in an ecology of fears that is far more complex. But in the framework of this text let us stick to the obvious connections for now.

Once fear is installed it is hard to get rid of it. It settles itself as a strong conviction. This means that it does not make much sense to address fear as such, directly. We must take some detours. Fear is the result of practice and indoctrination. After you experienced whatever kind of violence, mental or physical, or after a specific danger is convincingly and repeatedly impressed on you, you will know that fear forever. The competitive capitalist economy is very helpful in creating the potential of a danger that everybody poses for one another, suggesting that we are alone and vulnerable and in ultimate and urgent need of protection—a protection that we can buy at a high cost—either collectively in the form of laws and the law enforcement provided by the army and the police, or privately in the form of security tools, gated communities, and bodyguards. The prevention of and protection from the destructive consequences of the system are mediated via a whole arsenal of insurances on offer to secure our health, home, car, job, studies, liability, etc., or to prevent the loss of our physical capacities, income, or even oneself (sudden death). Any risk can be insured against.

Only a change of practices can dissolve fear and the fear of fear. The good news is: Neoliberal capitalism is not the only economy we can operate within. There are more, one of which is even bigger in size: the money-free economy.

THE NOT-FOR-MONEY ECONOMYLet me first define what an economy is: An economy is all that is exchanged between people. It is what people produce, or, better, it is the movements between people, whether these movements stink or smell good—for it to be economical, its quality is of no importance. All operations by an individual or between people—whether a talk or a walk; consumptive (the usage of shoes and the pavement when we walk) or productive (the flow of communication in a conversation, the travel from a to b, whether b is a bar, a meeting, a job, a social visit)—all the movements that keep us active. The motor of the economy is nothing other than what we do. In short, it is the sum of all our activities, whether productive or nonproductive.

The not-for-money economy is an economy that operates through a wide range of activities that are not valued in terms of money: the sharing, giving, borrowing, and hospitable exchange of services, goods, and activities. This for-free economy is huge. It is bigger in quantities of exchange and quantities of time than the money economy. We do a lot for free, without thinking about valorizing it, or giving it a value. We do it just because we do it and we think it is OK to do so. It is not at all our goal or purpose but mostly we get something in return, of material and/or immaterial value, like goods, services, friendship, colleaguealism, love, support, a life lesson, protection, self-esteem, joy, help, company, the same generosity, etc., etc. Quite often these things are of such a high value that we tend to call them invaluable! But, again, this is not what we are after, we do it because we think it makes sense. There is some beauty and elegance in this.

Can we expand this economy of generosity? Can we expand this generosity to more people than a close(d) circle, and can we open it up to a wider range of goods and services?

We currently limit our operations within this for-free economy to small groups with whom we share affection(s), like family, friends, colleagues, and shared-interest groups. But in most of our activities we use solid protection. To protect our interests we organize the inclusion (selection), we privatize, we lock things away to protect the exclusive use of our private property. And with our taxes we hire state protection, police and soldiers and the judiciary, because we think we have the right to keep our property away from the use of others, and this despite the fact that most of the goods we own are ‘stolen’ (as to pay too little for something, too little according to your own standards of living, is a form of stealing). It looks like there is a lot of projection in the protection, as the owners of (stolen) property—the fruits of that ugly, basic accumulation—constantly imagine that their things will be stolen.

How can we get the fear of the other out of us? How to get rid of the belief that l’enfer c’est les autres, hell is other people, or, another old-fashioned adage, that Homo Homini Lupus, people are wolves for each other?

I would rather say: people are much nicer and much smarter than they allow themselves to be treated (one, as criminals that steal from each other and, two, as children who do not know how things work, who are unable to organize themselves and therefore need to be led and need to be chained to numerous rules to protect themselves against themselves and against others).

THE REVOLUTION IS NON-LINEAR / A LIQUID REVOLUTIONTo follow me in this quest for a for-free economy you have to realize that I am not proposing a total and irrevocable revolution. It is a revolution, absolutely, but one that starts small and then spreads like water, infiltrating, borderless, able to solidify as well as to evaporate. It is flexible and has a high dissolvability. It can take in, absorb, assimilate, and transport a lot.

I invite you to imagine that something simple and small can become complex, like Alan Turing’s zeros and ones. To think whimsically, not linearly. Do not think of a concept first and then how to realize it, but think from what is there, and all that could be there, and then let it work. Think that we do not have nor do we need to have solutions for everything from the start! Think small: there is no need to change the whole world at once. Think baby steps, think close. Think how to revolutionize yourself, not how to mass revolutionize others or how the world should have to revolutionize itself.

It is we ourselves who need radical change. And a radical change is nothing else than changing something into something radically different. To revolutionize yourself is to undo yourself from yourself, from your beliefs and convictions, from your god complex, the complex that whispers a misleading song in your ear, telling you that you are right, that you know how things work, that you know who you are and will always be and what you need. In the undoing process, we will see how lost we are in this complex of beliefs and convictions, and, at the same time, how desperate we hold onto them, fiercely defending the prison we created for ourselves.

I invite you to try thinking together about what I will propose hereunder. Not by rejecting it, or by taking counter positions, not by playing devil’s advocate, not by imagining all kinds of arguments as to why this should be impossible, but by thinking the unthinkable, by adding suggestions, solutions, or by asking questions (that do not imply an opinion).

Let me give an example of how not to think: How would we deal with the process of decision making in the case of massive projects like where to build a new airport or how to plan national roads, organize the trains, airports, and hospitals or any other big infrastructural project? The answer is: That is not our problem right now. We must first build up the for-free economy from a small scale. When there are many of these relatively small for-free economies we will live in another world than the one we live in now. We do not know the potentials of this sharing society yet. We do not know how this new society that allows less protection and more sharing would organize the necessary massive projects, but what we do know is that they will do it completely differently from how we can imagine it now.

Although, I can imagine how people that work in teams—and many do, like a train team who run a specific track, or a team in a car factory who run the electricity in the plant, or a set of schoolteachers who run a part of a school, or the operation unit in a hospital or the nurses of a certain unit—can easily organize themselves, fulfill their targets, not by doing what their managers plan, but by organizing themselves. The only thing they need to do is to take and share collective responsibility, for the care in the unit, the electricity in the plant, for things to work well, better than ever. They do not need anything else other than the ability to organize themselves together as a flexible workforce.

I invite you to stay close, to not think too far ahead—even if, as Ludwig Wittgenstein said: It is so difficult not to think too far ahead. Or, Louis Althusser: There is nothing more difficult than to address that which is obvious. Let’s think with Alan Turing: We can only see a short distance ahead, but we can see plenty there that needs to be done. Or, Richard Feynman: Most people imagine what is not there, I try to imagine what is there.

All four express the beauty and elegance of the effort needed to concentrate on what is close, on that which is near, that which is almost tangible.

EXTRAPOLATING GENEROSITYLet us try to start from the generosity between two people and then imagine an extrapolation to infinite numbers. Think of two people: you and me. We are already enough to start with. We try to share as much as we feel like sharing. There are no obligations to share. No need to share everything. No need to share equally. Many actions are not comparable, let alone valorizable. Do not oblige your fellow sharer to share things she or he does not want to share, nor press the other to share things with you that she or he does not want to share. Do not valuate any sharing or make it payable, not even the sharing of goods and services that are consumed, like food or gasoline in a borrowed car. Let the sharing be for free and be accompanied by as little rules or codes of behavior as possible.

In general let there not be too many rules or principles. Let us try to do without. We the people need not be protected against us, the people. Again: as we the people are much nicer and much smarter than we allow ourselves to be treated, we the people will free ourselves from ourselves.

This new society that has the infinite capacity to neutralize differences, behaves like water. We are not the same and we do not want to be, we do not look alike, we do not think alike, we do not feel alike, we do not know alike, and we do not survive alike. Let this be. This is a celebration of differences in a society of abundance.

Gradually share more, either by increasing the intensity of shared use or by adding more goods and services, more time and space. Gradually allow more to take part, as it is very likely that not only A shares with B, but A and B also share with others, A with C and B with D; and A, B, C, and D meet each other in relation to the same shared space or the same shared instrument. But C and D do not only share A’s and B’s things, they also bring in their own shareable spaces and instruments. Together, all four now have more than they did alone.

Imagine that all four can have different sharing allowances with each other. Imagine also that the original owner, the sharietor, can always refuse use at any moment to any of the others. Imagine also that the sharietor can refuse any of the others, the sharers, use of the instrument, the shared, permanently. It must be very imaginable that from A, B, C, and D the proliferation of the group of sharers becomes exponential. And soon different groups will overlap and intermingle. Maybe they will start sharing money and opening a common bank account, a mountain of money to which the whole group of participants who feed the bank account has access to. Let us try to avoid rules and organization or branding. It is a practice, a decentralized practice that develops its practices while practicing, while emerging as a bigger world of sharers, a moveable world, like water. And when the group grows, its characteristics diversify and more goods, services, time, and space are shared.

We start our for-free economy with two independents, no money, no management, we do what we want and we do it how we want to. We become ten, 100, 1000, 10000, and so forth. Our needs become bigger, we have to organize transport, education, a hospital, our own bank. But we will not copy, we will rethink, redo every organization, we will think the provisions for these functions differently, radically differently, as their organizational structures are still based on nineteenth-century industrial society’s need to train for obedience and dependency. This means that we change things into something else! All without the need for a centralized form of governance. And it all functions in very many variations. We do not need the standards and protocols of the old society. We neither need representative institutions like in a democracy, nor any representations. The only one one represents is oneself.

I would prefer that there was no place to vote either.

We share but we do not count time. We will not be a time bank: my hour working in your garden is your hour working on my mouth. No, no valorizing scheme. Just share. It does not matter. No calculations, no negotiations, only unmitigated sharing. Not: I shared 100 books with you and you shared ten with me so you owe me ninety. No way, that is from another world: the old world, the world we are currently living in.

All this sharing will make lives cheaper. Over time, the sharers will realize that they spend less. Less spending is a way of creating income. And they will realize that they can do without governmental administration and protection, without paying taxes, without insurance, without rules, without leaders. Without the useless spending that made us run the rat race of everyday life to barely make ends meet. Without the whip of the fear of losing your job. Without the stress of too little time to get too much done. This new society takes the invisible commander that we are for ourselves out of service. We will stop being a slave of society and of ourselves. We release ourselves from the fear of ourselves. The fear will be replaced by sharing, by a new practice. And we will not change overnight, it will take time, we will develop gradually, first with two then ten then 100 and so forth. First with one thing, then two, then slowly more. Because we are the economy, the production, and the productivity. We make the world go around. We can create and organize many supple things, allowing variations, allowing unexpected results. We can do without protocols, standards, and standardizations, we want variations that fit our differences, we want things that can become something else other than what we expected them to be. We are no longer afraid, because we are equipped, equipped enough to embrace the unexpected, to reinterpret and to redirect expectations, like water, we are like water.

We do, we will make, we will create, we will develop, we will shape, we will propose.

We will do as we cannot not do.

Who wants to join?

Who wants to share with me?

Shall we build a mountain of money, open a common bank account?

janritsema@mac.com

[1] Quoted from: http://www.forbes.com/sites/laurashin/2014/01/23/the-85-richest-people-in-the-world-have-as-much-wealth-as-the-3-5-billion-poorest/ (accessed October 29, 2014)

—

—

The dutch theatre director Jan Ritsema (1945) makes theatre that triggers these strange moments where thinking and performing meet eachother. Ritsema directed repertoire from Shakespeare, Bernard-Marie Koltès and all the time again Heiner Müller, and he dramatised novels from James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, Rainer Maria Rilke and others. Pieces made in cooperation with others, like Weak Dance Strong Questions, TodayUlysses and Pipelines, a construction have a huge success in Europe in the nineties and tens. Ritsema is not interested in the big illusion and fiction machine through which theatre often is represented, but in the live presentation of bodies on stage that think and that provoke thinking. Theatre as the place where actors and audience in their live gathering can think together. He started dancing when he was fifty. Made a solo. Was invited by Meg Stuart for several ‘Crash Landings’, worked with Boris Charmatz in his Entrainements project in Paris and in a Bocal presentation and made Weak Dance Strong Questions with Jonathan Burrows. Teaches at PARTS, the dance school of Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker since it started in 1995. In 1978 Ritsema founded the International Theatre Bookshop and publishes more than 400 books. In 2006 Ritsema founded the PerformingArtsForum in France near Reims (www.pa-f.net), an alternative artists residency, run by artists. In 2010/11 Ritsema dances in Xavier le Roy’s new piece, ’Low Pieces’, created ’Ça’ in Paris, and ’Oidipous, my foot’ in Brussels, Essen and Graz.

—